Yesterday we returned from a five-day trip to

Kruger National Park and the Hoedspruit Endangered Species Center in South

Africa with over a thousand pictures and some new wildlife experiences.

This trip, we set out to see carnivores, so we

headed to the north of the park where lions are less prevalent and cheetahs,

leopards, and hyenas enjoy the lack of competition while rare antelopes such as

Sable and Hartebeest enjoy the lack of lions eating them. We started in Skukuza

camp, which is still in the south of the park and from there embarked on a

game drive with a guide named Robert.

The first thing we saw was a breeding

pack of hyenas. Robert explained that hyenas separate their cubs into

age-appropriate groups so that they don’t compete for food, and that a cub will

be fed not only by its mother but also by other members of the pack, practices

to which Robert attributed the very low infant mortality rate among hyenas. Sure

enough, after we had watched and taken photos of this lady, we realized that

there was another nursing mother on the other side of the road with two very

young, all-black cubs who had yet to gain their characteristic spots.

The first thing we saw was a breeding

pack of hyenas. Robert explained that hyenas separate their cubs into

age-appropriate groups so that they don’t compete for food, and that a cub will

be fed not only by its mother but also by other members of the pack, practices

to which Robert attributed the very low infant mortality rate among hyenas. Sure

enough, after we had watched and taken photos of this lady, we realized that

there was another nursing mother on the other side of the road with two very

young, all-black cubs who had yet to gain their characteristic spots.  Robert also noticed something in one of the trees

as we passed by, and when he backed up to show it to us, it turned out to be one

of the most impressive feats of safari-guidery that I have ever seen. In the

dark and while driving, Robert spotted a flap-necked chameleon, a tiny little

fellow who looked so much like the leaves around him that Robert had to point

for ten minutes before everyone in the vehicle had seen it.

Robert also noticed something in one of the trees

as we passed by, and when he backed up to show it to us, it turned out to be one

of the most impressive feats of safari-guidery that I have ever seen. In the

dark and while driving, Robert spotted a flap-necked chameleon, a tiny little

fellow who looked so much like the leaves around him that Robert had to point

for ten minutes before everyone in the vehicle had seen it.

On the fifteenth, we left Skukuza and headed for

Mopani camp, which is named for the famous Mopani tree (in which lives the

Mopani worm, which is considered a delicacy) and is further north in the park.

As we drove up to our camp, we saw teasing symbols—there was a dead impala in a

tree, which can only mean one thing, but the leopard had left his kill and was

likely afraid to return until the humans had stopped guarding his dinner.

It was a good day for other sightings, though. I

have seen a lot of hippos, but always mostly submerged. On the fourteenth I saw

my first hippos out of water (courtesy of the chilly weather) and the next day

we looked out over the river from the safety of a hide to see a huge breeding herd

basking on a little island that likely disappears during rainy season.

It was a good day for other sightings, though. I

have seen a lot of hippos, but always mostly submerged. On the fourteenth I saw

my first hippos out of water (courtesy of the chilly weather) and the next day

we looked out over the river from the safety of a hide to see a huge breeding herd

basking on a little island that likely disappears during rainy season.

The next day, on a morning drive with a guide

named Amos, we saw a serval and some black-backed jackals, each of which was

too quick to photograph. We also came across this lone female hyena taking seriously

the command of so many parents for their children to finish everything on their

plates. She was gnawing on the last of the skin of an elephant carcass—the elephant

was killed in January when it was struck by lightning, and while I never like

to see an elephant in turmoil, it was amazing how the detrivores continually

made use of the resources available to them.

It was also a good day for birds. We saw a group

of six juvenile ostriches—I saw my first ostrich in the wild on Friday and

couldn’t believe its size even after having seen them in zoos, and even the

young ones were gigantic. But even more exciting than the ostriches were a

smaller and less-known bird which we came across later. In a group of four,

crossing over the road by foot, were the endangered Southern Ground Hornbills.

These large, flighted but mostly ground-dwelling birds are quite rare, and in

fact only 1500 individuals are estimated to exist in South Africa, so we were very

lucky to have seen them.

On the seventeenth, we woke up early

to prepare to leave Kruger for the Hoedspruit Endangered Species Center, and

saw yet another hyena—this one was also nursing, but right in the middle of the

road. She seemed very comfortable with the cars going by and also stopping for

photos.

So we had seen several hyenas,

jackals, and even a serval but none of the majestic big cats. We had seen a

leopard’s kill and also seen a spot in the ground where another leopard had

dragged a kill across the road, and we had heard reports of lions and leopards

and even caught a short glimpse of a leopard in a far-away tree, but sometimes

it’s enough to except the little signs even if you can’t see the actual animal.

As we neared the gate, I noticed a large herd of impala—and of course, why

would impala just stand there, if a predator was nearby? Still, they looked

alert, and right after we passed them I thought I saw something lying in the

riverbed. I asked if we could back up, apologizing in case it was just an

impala and I was making us stop for nothing.

As I have mentioned, I used to

dislike the idea of animals eating one another, but there are two sides to every

story. Leopards have cubs to feed too. Hyenas separate

into nurseries and apparently nurse their pups right in the middle of the road.

So in the end, everybody’s just trying to survive. Sometimes an impala gets

away, and sometimes a leopard gets to eat. I’m just glad he chose that riverbed

to rest in after the hunt.

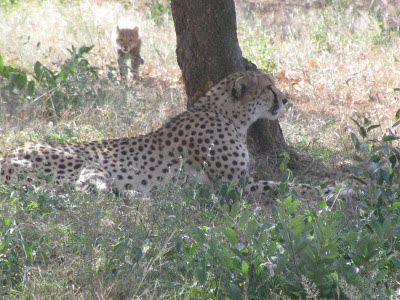

At the Hoedspruit Endangered Species Center (HESC), the goal is to preserve endangered species such as ground hornbills, African wild dogs, caracals, and servals, but the focus is and has always been on cheetahs.

The HESC includes breeding programs in which cheeta

The HESC includes breeding programs in which cheeta

And speaking of the wild, the HESC

partners with Kapama Game Reserve, a wild and unregulated piece of land where

animals are free to avoid us seeing them, to arrange game drives there and

occasionally to release animals onto the reserve. We were on one such game

drive and were seeing a lot of common duikers (a small antelope some may

remember from a particularly uneventful night drive of two years ago) when we

topped off our trip with one last huge sighting. In contrast to my unsure

reports of something lying in the riverbed when I saw the leopard, Caleb drew

attention to his find definitively.

“Lion. Lion lion lion.”